A year ago, I sat in a State and Local Politics class listening to several male-identifying classmates engage in a heated debate over public education policy. I listened, on the periphery, until I heard something with which I disagreed. Then, I jumped in, eager to share my own input into what had become a lively debate.

My classmates stopped talking, rolled their eyes and looked at me. One summed it up: “Don’t get mad,” he said.

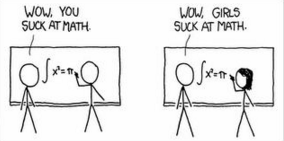

As a female-identifying student, this epitomizes one of the many (and seemingly weekly) interactions I have that attempt, either consciously or not, to belittle intelligence and devalue my contributions in the classroom. Although I shared the same tone and style of participating, my contribution was dismissed as a woman nagging. My vehement male classmates weren’t dismissed on account of their tones, but I was.

This interaction is not a fluke or an accident or a rarity. It happens every day, in classrooms all over my campus and beyond, informing the way we speak to each other and whose voices are deemed important and, in turn, who gets the opportunity to make decisions for themselves and for their communities. Simply put, it matters if people are silenced during a debate in a classroom. And more often than not, they are women.

I don’t want to discount the inequalities in education experienced by people of color every day. Research shows that these inequalities are both macro and micro, in the way students of color are disproportionately tracked for vocational or non-college preparatory paths in school and in the way that students of color are less likely to challenge authority figures or raise their hands. In this blog post, however, I want to focus on the discrepancies in treatment for women, although identities (such as race and gender) are clearly intersectional and certainly affect treatment. More on that in a later post.

My inspiration for this post comes from a rare experience I recently had: my Politics of Reading course drew up a charter, requested input from every single individual, and discussed what makes a good course. In this class, we agreed that affirming others is important, that ensuring a speaker does not interrupt another is mandatory, and that responding to a person’s comment is necessary before moving on to another. Would we have had this conversation if the gender proportions were flipped — if women did not outnumber men in this class more than three-to-one? I do not wish to make the conclusion that men are not sensitive or good listeners or capable of participating in open and inclusive class discussion. As a person frequently in class with many people who identify as men, I know they can. But this is significant — because it is women who are most often silenced.

I want to speak to my experiences as a woman who is otherwise very privileged — most visibly, as a white person. Many studies have sought to explain or describe differentiated gender treatment within schools. In one study, two researchers studied the gendered treatment of children in elementary schools. Sadkers and Sadkers studied the ways that students are treated differently during classroom discussion. They found that both white males and males of color were more likely to be heard than white females, and that women of color were least likely to receive attention from teachers (Sadkers and Sadkers, 2009). They also found that after asking a question, teachers often give boys double the time to answer than girls. As Sadkers and Sadkers note, this is important: “later in life, in the working world, salary received is important, and the salary levels parallel the classroom.”

They’re not the only ones to see the connection between gendered treatment in school and disparate gendered salaries; among many researchers, Dr. Roslyn Michelson found that women make less than men at every level of educational attainment. In STEM jobs, which have thought to be the most up-and-coming and lucrative in recent years, women (who are equally educated) make 86% of what they pay men in similar jobs (Mickelson, 2008). Even in jobs thought to be traditionally for women, such as nursing, men make more money; Mickelson found over $100 difference per week as of 2008.

There are so many more studies that describe the discrepancies in gender treatment and that offer some explanation for its ripple effects. But there is no justification for disparate and unfair treatment to be found. And I’m left saying to myself, a woman with so many privileged identities who has been told she is smart and capable nearly every day of her life, if it’s happening to me, it’s happening to others, and not all others have the resources or the support I do to demand something better — to argue back, to stand up for myself and, as I enter the real world, demand equal compensation, knowing that I am not part of disadvantaged groups also facing discrimination in myriad other ways.

Research and evidence are important to the creation of a solid argument, so that is why I included it, but felt like I needed proof for the male readers out there who might think I’m overreacting or call me aggressive or fail to take to heart the broader point of this post: what you do matters. The way you treat students who identify or appear female affects their ability to succeed, and you’re only partly to blame. Indeed, there is a structural disadvantage for women in education who are taught that their voices matter less, and while the system undoubtedly must change, the classroom environment can be improved for individual women every day when those whose identities have long been favored can instead choose to listen and affirm, and teachers can choose to wait and support. Additionally, teachers: begin classroom interactions with a conversation about what students need to feel welcomed and included in classroom discussion; it is your responsibility, too, to make classrooms a safe space to foster dialogue and promote often discounted voices.

Don’t call me aggressive for choosing to ensure my voice is rightfully heard.

Thanks so much for your passionate post on this important topic. I’m so sorry and so frustrated to hear about the direct gender bias you experienced in your recent class discussion. There is definitely a double standard when it comes to the perception of women and men’s behavior in a work and school environment. Women are considered bossy when a man would be seen as a leader, and nagging when a man would be considered insightful and thorough. I appreciate the concrete research that you used to support your point that this differed treatment begins in classrooms at a young age. It is unfortunate to see that just as differed gender treatment in the classroom parallels the gender wage gap later in life, so does the differed treatment of individuals with intersecting disadvantaged identities. Women of color make the smallest percentage of a white male’s salary — with Hispanic/Latina women making only 54% compared to white women’s 78%! See here: https://newrepublic.com/article/121530/women-color-make-far-less-78-cents-mans-dollar. The correlation between this data and the data you presented on the disadvantage that women of color especially experience in the classroom just goes to show the importance of equal treatment in the classroom. I love the emphasis that you put on that what we all do matters in addressing factors inside and outside of the classroom that tell women that their voices matter less. It makes me wonder how can we support teachers to make sure that all voices are heard in their classrooms? The blame of gender inequality of course does not fall completely on teachers or any individual system, but how much of a role are teachers playing in perpetuating differed gender treatment even when they don’t realize it? What strategies can we provide them with to combat inherent biases that they may have not only based on gender, but a myriad of other intersecting identities?

LikeLike

Thank you for this post, mayjax. I wish we could start earlier in education (at the very least, in high school, if not earlier) in addressing this issue. I think that you are right that women and girls are expected to elbow their way into classroom, business, or personal conversations dominated by men and boys (or risk going unheard); but are simultaneously and unfairly penalized for doing so. As you mentioned, women tend to be called “bossy” (even when they are the “boss”!) as well as “nagging,” which you mentioned. Some other gender-coded words are “hysterical” and “shrill,” as well as “pearl-clutching.” All of which means the content of what is said is dismissed and disparaged by pointing to the gender of the person speaking.

LikeLike